On Tuesday, March 8th, I was absent-mindedly surfing the web in my London apartment. Outside my room, my roommate and a couple friends were goofing around with coloured cotton balls. I had joined them for a while, but my mind was occupied with something else. I opened my email inbox. “Yale Medical School,” I typed into the search box. I did not expect any news, as the official date for acceptance notification was not until two days later, or so I was told.

Maybe it was my fingers running across the keys, or maybe it was the little rat running in the back of my mind, but I was brought back to my interview day a month earlier. It was snowing that day. In fact, it was snowing so hard that my flight from Toronto was delayed by two hours, which meant I missed my layover flight from Detroit. Thankfully, there was another flight later that day. That, however, delayed my arrival at New Haven, so I missed the last shuttle to Yale. It was a one-hour ride from the airport to Yale campus, so when I called the shuttle service at Bradley airport I was already thinking of alternative ways to make my way there.

“Is this CT Limo?” I asked the person who picked up the phone. CT Limo was the name of the shuttle service.

“Yes,” said the operator.

“Hi, is there another shuttle left?” I asked.

“Let me check…” I held my breath.

“We have one left. He leaves in ten minutes.”

“Great! How do I pay?”

“Uh…ask someone at the airport. We should have a rep there.”

They did not. No one at the terminal knew how CT Limo operated or who was really in charge. All they knew was that a shuttle arrived at certain times during the day and carried travellers to and from the airport. But sometimes, it did not arrive as expected. In fact, it seemed like CT Limo missed about ten percent of all of its promised departure times.

I was becoming increasingly anxious as I waited on the promised platform. Shuttle after shuttle came and passed, bringing passengers to the local car rental agency. The day waned. It stretched a red yawn right across the horizon before falling into a deep slumber. At half past six, a white van bearing what looked like a Mercedes logo pulled up. I had a déjà vu to the time in China when I travelled in a black cab (a privately owned taxi, much like Uber but not as accountable or legal).

The driver stepped out. He did not speak much English. He went for my bags. I hesitated. What the heck, I thought to myself, and stepped into the van.

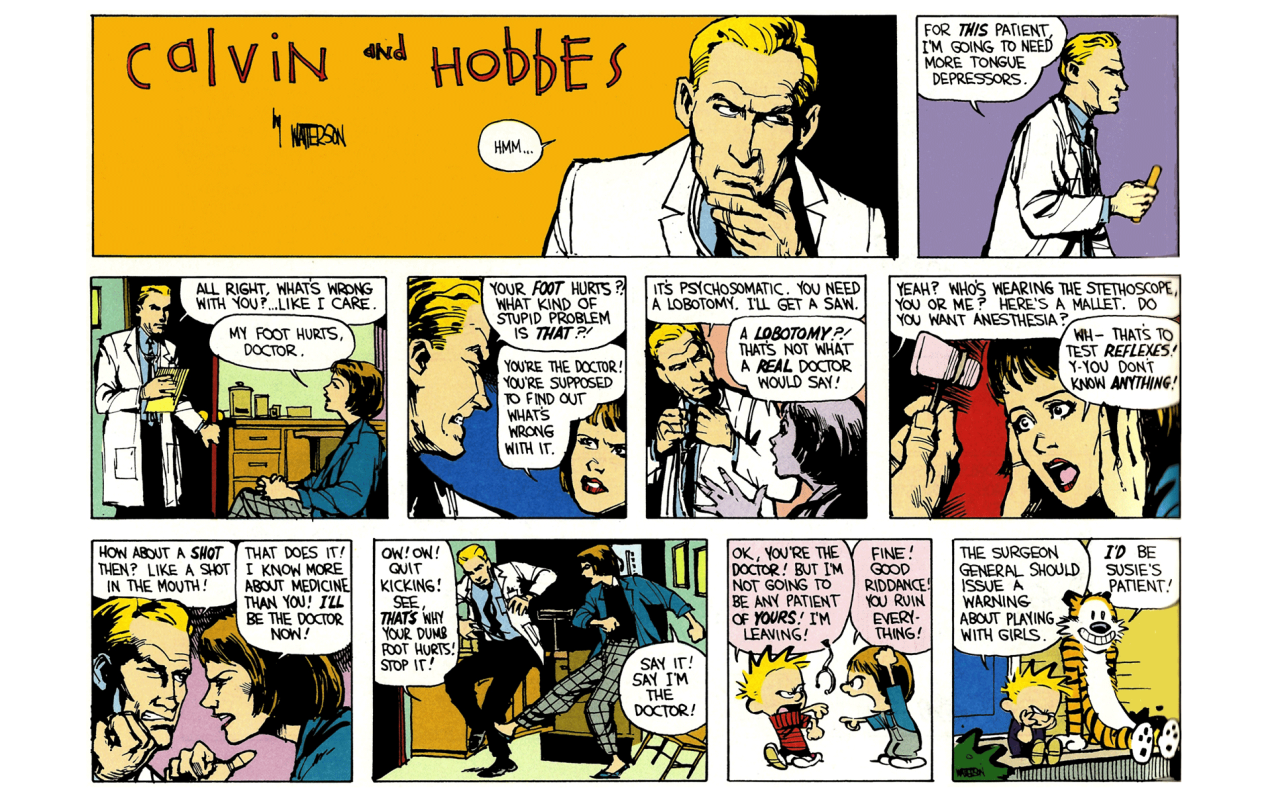

Yale Medical School is located in New Haven, Connecticut. Since its founding in 1813, it had served as the training grounds for many outstanding physicians, from Harvey Cushing, the father of neurosurgery, to Vivek Murphy, the current Surgeon-General to President Obama. When I arrived that night, I met with a few students whom I had been in contact with. One of them, Aaron (names changed), graduated from Yale as an undergraduate and the other, Raj, was from Stanford. We sat in the cafeteria of the medical school residence. In the studio next door, a ballroom dance class was underway.

“Thanks for chatting with me,” I said. “I know how busy you are.”

“Not really. We just finished an exam,” said Aaron. “We’re catching Deadpool later. I’d ask you to come but you probably need your rest for tomorrow.”

I agreed.

“I have a few questions I’m dying to ask,” I said.

“Go ahead.”

“How are you liking the Yale System?”

The Yale System had been Yale Medical School’s educational philosophy since the early 1900s when it was first proposed by Dean Winternitz. Under the System, classes are optional, exams are anonymous and self-directed, and medical students can take classes at any of the other Yale schools. I already had plans to study history and law if I had the time.

“We love it,” they both said, summing up what I had read online. Over the next hour, we talked about how they had taken advantage of the System, what classes were like, and what research opportunities there were. I could tell that they were very enthusiastic about their school and the Yale System. Their passion was infectious. At 9 PM, as I got up to leave, I remembered one last question.

“I understand that you’re Canadian,” I said to Aaron. “Are there many international students here?”

He thought about this for a while.

“I think there are ten of us. Five are Canadian. But…” At this, he hesitated. “…we all did our undergrad in the States.”

Ah well, I thought to myself, I guess I won’t expect too much. I had known that the majority of the medical class already had a postgraduate degree. Compounding on the international factor, the odds were not good. But I resolved to enjoy this experience as much as possible.

“Thank you for your time, guys. I really appreciate this.”

“Good luck tomorrow!”

At 8 AM the next morning, I walked from my Airbnb apartment to the medical center. As I walked, I marvelled at the day. The sun had poured itself onto the streets and pavements of Yale’s campus, and the air had a balmy breeze with a hint of spring.

The night before, I had made up my mind to accept whatever outcome that came. As a matter of fact, I had adopted that mindset even before I began my application in July. Truth be told, there are many reasons why students apply to medical school, and wanting to become a doctor is only one of them. Another reason is that we are afraid. We are afraid of a future of uncertainty, of experiencing a setback, and of coming to grips with our limitations. More than anything else, we are afraid of losing significance, of our sense of pride. I was with my friend the day he received an interview invitation to one of the Canadian schools. I saw his hands shaking as he opened the email. Gosh, I thought to myself as I watched him, do I base my identity on my success so much as well?

In Aequanimitas, William Osler, the great Canadian doctor, co-founder of Johns Hopkins Hospital and one of my heroes, discussed the single most important trait of doctors. He called it “imperturbability”, the ability to remain calm and grounded in all situations. Just as in the biblical parable of the man who builds his house on solid rock, a doctor must also build his identity and principles on firm foundations. The ability to succeed only constitutes a portion of that. Aequanimitas, I repeated to myself as I entered the admissions office.

The first people I met that day were the other interviewees. Because it was a Wednesday, there were only six of us. Three of them were post-graduates. Then the Dean of Admissions, Richard Silverman, arrived. He was an elderly gentleman with white hair and round-rimmed glasses. Beneath them, his eyes flashed with the unmistakable glint of intelligence mixed with a cheeky playfulness.

He talked. He joked. We laughed nervously. “You guys look tense,” he said. “You know, there was once a girl who interviewed here. She was so eager that when she got into the interview room, the interviewer asked her the profound question ‘did you find the place without any trouble?’ to which she answered ‘Yes, no trouble at all’ and launched straight into ‘which reminds me of a time in my research experience…’”

We all laughed. I knew we were thinking of the same thing: pre-meds are such keeners. Then we caught ourselves and smiled sheepishly.

“This is a chance for us to get to know you, and for you to know us,” concluded Richard Silverman. “So enjoy yourselves! You guys will do just fine.” Then he left with a curious wink.

Later that day, I stood outside my interviewer’s office in the Department of Surgery. I looked at my watch: Five to two. I’ll wait for five more minutes, I thought to myself. A lady wearing a white lab coat walked past.

I had already had an interview that morning. My interviewer, an upper year medical student who was an aspiring pediatric oncologist and amateur chef, had come off as a friendly and genuine person. In fact, ever since I met the two students from the previous night, I had begun to form the impression of Yale students as unexpectedly humble, quite unlike the stereotype of students from elite institutions. (Although, I might add that this could only apply to postgraduate schools, and also make mention of my extremely small and self-selecting sample size.)

That morning’s interview had gone smoothly. Yale used a traditional, one-on-one interview format, which allowed for deeper conversations. My interviewer himself had chosen to print off pre-set questions which he had made based on my primary application, but our conversation often diverted depending on what he wanted to know more about. Our discussion ranged from the humanities in medical practice to the idealisms of new doctors.

This afternoon’s interview was going to be different. Dean Silverman had introduced our interviewers by name that morning, from which I took away three things about mine. First, he was a big deal in the department, whatever that meant. Second, he was famous for wearing bow ties; in fact, one of them had sold for $3000 at a charity auction. Third, Silverman had chuckled when he read his name. Whatever that meant.

2 PM. I knocked on the door. Nothing. I knocked louder. “Just a second!” came a yell from inside. “Alright!” I yelled back. What a way to make an impression, I thought to myself. The door opened. I was greeted by an elderly gentleman with thick glasses. I glanced down. He was wearing a brown bow tie.

“Come in, come in,” he said.

I stepped into his office. It was a surprisingly small space made even smaller by the assortment of items piled on his desk. Books, files, stationery and other objects I did not recognize took up residence at seemingly haphazard spots, and a large but old flat screen computer monitor took prime location at the center. A single large window faced the East, upon which a firm layer of dust softened the gentle sunlight that floated in. There was an old wooden rocking chair facing his desk. It did not look comfortable.

I found his office so curious that the first thing I did was to slump into the chair. A jarring protest from my hip against the hard backing reminded me that I was at an interview, so I squirmed to the edge of my seat and kept my back as straight as I could.

“So you’re from Canada?” was his first question.

“Yes, but I was actually born-”, I began, but a loud clicking sound interrupted me. Kr-kr-kr-kr-kr-kr… It was the heater tucked away in the corner of the room.

“I spent my childhood in Canada too,” he said. “Victoria Island. You know that, don’t you? We used to go kayaking and we’d see whales.”

In ordinary circumstances, I would have been happy to hear his story. But because it was an interview, I was also hoping to present my own. He apparently had different ideas.

“We would kayak off Nanaimo, and sometimes we would see seals.”

“Seals that far south?” I asked. I could not stop myself. I had gone kayaking in the same area, and I never saw whales nor seals.

“Yes…but I left when I was ten,” he said. I expected him to go on.

“So what do you do for fun?” He asked suddenly.

I was just about to carry on the conversation in the same tone that he had: relaxed, casual and somewhat aimless. But I caught myself just in time. Was this an interview question? Has the interview finally started? Violin, writing, martial arts, I thought to myself and said so.

“What kind of martial arts?” he asked.

“I’ve been practicing Seikido – a martial art based on Taekwondo and Aikido – since freshman year. But I’m also hoping to explore some Chinese martial arts. I’m going back to China to do that over the summer.”

He nodded. Over the next hour, I found an unusual pattern in our conversation. Whenever I began to talk about my “selling points”– the Science Case Competition, Backyard Labs, Friends of MSF – I sensed his attention drifting. I had to cut a few of my points short because of it. On the other hand, he seemed interested in what I thought to be irrelevant material.

“So what’s your favourite course?” he asked.

I smiled sheepishly. I had prepared an answer involving an especially hard course I had taken and how I had shown perseverance by succeeding in it. But having interacted with him for a while, I decided that that answer would not suffice.

“I picked up the Lord of the Rings series a few years ago and loved it,” I said. He nodded emphatically.

“I loved it so much that, in one summer, I read the book series twice, watched the movies six times through, and watched a ten-hour documentary on it.” I could sense his interest growing.

“I learned that Tolkien loved trees. His description of forests and the Ents are some of the most evocative. So I took a course, Evolution of Plants, to better appreciate his work.”

We both laughed at how ridiculous I sounded. But after interviewing at a few schools in both Canada and the States, I think this might be one of the most distinguishing criteria between the two. Canadian schools tend to emphasize “traditional doctoring qualities,” so scenario questions and questions about volunteer experience were common. In the US, I had a lot more questions about my passions, research and leadership activities. In fact, one of my proudest achievements, creating the Science Case Competition, was not even mentioned during my Canadian interviews.

“Tell me about your research,” he said. I explained how I was using machine learning to model how humans sense touch.

“When you model the receptors,” he said. “Which neurons are you modeling? Merkel or Meissner?”

I blanked. I wanted to shoot myself in the foot. I had read it before, but because it was not relevant to my model from a computational standpoint and I had not taken a physiology class, I was not sure. Fifty-fifty chance. I thought it was Merkel…or was it Meissner? I can’t believe I missed this when reviewing! Should I guess? I decided that I had better be honest.

“I’m actually not sure,” I said with ironic confidence. “It’s not essential to the model I’m designing. All that matters to me is that the neurons I model are the ones involved in tactile discrimination. They adapt slowly to changes in pressure, so in the lab, we just refer to them as SA-1 neurons.”

He nodded with a somewhat-satisfied-but-still-a-little-skeptical look.

“Neuroanatomy was the focus of my lab,” he said. “I’m not in the lab anymore. I’ve been focusing on education over the past couple of years.”

“I’m interested in education too,” I said. “As you can see from the science case competition…” I trailed off hopefully. Just ask me to tell you more about it! He nodded. I decided to drop it.

“Yale has the Anatomy Project that invites high school students into the anatomy lab,” I said. “I think it’s a great experiential learning opportunity for those students. I’d like to get involved in it if I come.”

“I created that.”

“Oh! Congratulations on its success,” I said.

“Yes, yes…a student of that program from one of the community schools, you know, underprivileged area, ended up coming to Yale Medical School.”

“That’s wonderful.”

“Yes, yes…” he said, more to himself than to me, then he looked at his watch. We were over time. “Well, it was a pleasure to chat with you.”

“Likewise,” I said. “Thank you for your time.”

I left that interview with mixed feelings. Later that evening, I received a message from my friend. “How did it go?” she asked. “I really have no idea,” I replied.

On Tuesday, March 8th, 2016, I was absent-mindedly surfing the web in my London apartment. It had been a hectic few weeks, with midterms, assignments and interviews all rolled into one continuous barrage. But I felt strangely peaceful amidst it all. Maybe it was because I understood the role of chance in this process, or maybe it was because of my friend’s muttered prayers that echoed in the dark, but deep down inside, I knew that I would be O.K. with whatever the outcome may be, that I would not lose my sense of worth, and that my success or failure doesn’t really matter in the grand scheme of things. I opened up my mailbox. “Yale Medical School,” I typed into the search box. I read the first result that came up. I blinked hard and read it again. It had gone into my spam box so I did not see it all day. But it was real. I couldn’t believe it. It was a letter of acceptance.

Being at Western and in the MedSci program I usually find myself looking for interview experiences, pre-med blogs (as ashamed I am to admit) and they all feel very rigid. I’m happy to finally read something like your experience and not feel like I need to wash my hands after. This was really well written and I wish you all the best on your next chapter in life.

LikeLike

Thank you! I hope to write a post to formally describe my preparatory and application process. Hopefully my experience can be helpful to future applicants.

LikeLike

As a physician and educator who interviews potential medical applicants, it was interesting to read your experience and also reflect on my previous admission process. I admire your ability not to define your self worth based on your achievements and accomplishments. They will never satisfy and are evident from your application. An interview is to understand the character and nature of the individual and I’m glad you let that shine through. All the best.

LikeLike

That is extremely encouraging. Thank you.

LikeLike